Medieval Animal Bones

The Various Voices of Medieval Animal Bones

Alice M. Choyke, Kyra Lyublyanovics, László Bartosiewicz (Budapest)

Introduction

Animals have been woven almost imperceptibly into the complex web of human existence from the very beginning of human history. From the far off times of the Paleolithic past up to the present day, animals have permeated every aspect of our ancestor’s lives and our own. Archaeozoology is the identification, analysis and scientific as well as socio-cultural interpretation of animal remains from archaeological sites. Such zoological finds have been exposed to ancient human activity (animal husbandry, processing etc.). Consequently, archaeological animal bone assemblages are “artifacts” that embody cultural processes. Often the human – animal interaction was purely practical, basically geared toward subsistence. Animals, coming from agricultural production systems were selected for slaughter, their carcasses divided between artisans working in various crafts and the butchers who sold their meat. These assemblages tell archaeozoologists what species were eaten, old the animals were, what they looked like etc. Marks of butchery reflect carcass partitioning both by the butcher and later during food preparation. These steps all involve choices fundamentally dependent on idiosyncratic cultural practices. These tend to be conservative and change only slowly unless radical outside pressure is exerted on food habits. The economically most important domestic animals, sheep (Ovis aries), goat (Capra hircus), cattle (Bos taurus) and pig (Sus domesticus) provided meat and milk for food. Their skins were made into clothing such as tunics and shoes or parts of equipment including straps for harnesses. The production of and trade in these goods formed significant parts of medieval economies. Bones, teeth, antlers and horns were also made into all sorts of utensils and ornaments, widely sold and used throughout every period. Before the advent of mechanization, horse (Equus caballus), donkey (Equus asinus) and mules/hinnies (Equus mulus/hinnus) as well as cattle were used to move people and goods long distances and pull heavy loads in agriculture, construction work and military transport. Draught oxen were widely used during the Middle Ages and much appreciated in heavy-duty work such as tillage and forestry work. Training good ox teams was a lengthy and tedious task, which made them especially valuable (Bartosiewicz et al. 1997). During the 16-17th century Ottoman Turkish occupation of Hungary great numbers of camels (Camelus sp., probably dromedaries), were used in shipping artillery supplies (Bartosiewicz 1996).

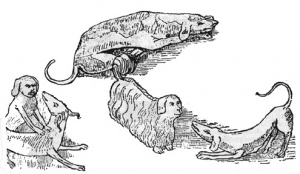

Hunting in the Middle Ages was restricted to the nobility but was always maintained as a mark of status and male identity. The most important game animals were red deer (Cervus elaphus) and wild boar (Sus scrofa). From archaeozoological assemblages and contemporaneous images we know that hare (Lepus europaeus) was also hunted, beaver (Castor fiber) and ermine (Mustela erminea), important fur animals, were also important in trade. Of course, all sorts of fish (Pisces), were also key items in the fasting diets throughout Catholic Europe. Even aquatic mammals, beaver and otter (?; Lutra lutra) could form a legitimate part of meals for Lent. Naturally, living with animals so closely, beasts existed for people on a mental level as well. For the elite classes the ownership of special breeds of dogs (Canis familiaris; Figure 1), highly-bred horses and sure-footed saddle mules as well as birds of prey used in falconry (chiefly Accipitridae) represented the closeness of the animal-human connection beyond everyday practicality. Importantly, such animals were also markers of status and prestige.

Conversely, some exotic animals in their strangeness roamed on the darker, more sinister side of people’s imaginations, frequently depicted in scenes of hell and the damned. From very early times, parts of animals were combined to make fantastic beasts also with their recognized qualities and topoi. Such beasts existed vividly in the imagination of medieval people. Perhaps, even if they were not encountered on a daily basis they were still an ever-present part of the culturally acknowledged structure and explanation of the world as it was understood by people in a given community at a given time.

Even relatively straightforward depictions of animals in medieval times display inter-specific mixing of body parts, so that even the well-known species such as horses may be shown with carnivore paws and dogs with hooves. This is in contrast with the Roman world where fantastic animals are depicted combining traits from multiple species but were clearly separated from the animals of everyday life, depicted very prosaically, realistically, as they would be described today in the western world. Finally, animals entered speech as metaphors about the nature of the world. It is on this level that the borderline between what is the nature of a human and what is the nature of an animal becomes fundamentally blurred so that angels have wings and devils cloven hooves or bird claws.

It may look surprising, that the first known osteological reconstruction took place within the context of scholarly research into unicorns. The skeleton of this animal (also depicted in Platina’s 1542 cookbook; Fahrenkamp 1986: 34), was assembled in good faith by Otto von Guericke (1602–1686) from the scattered remains of a mammoth (Mammuthus primigenius) and other extinct ungulates, recovered from a sinkhole near Zeunickenberg, Saxonia (Leibniz 1749; Figure 2). (Von Guericke was acclaimed for his famous 1650 Magdeburg vacuum experiment: two teams of eight horses were unable to pull apart the brass hemispheres whose air content had been sucked out).

Limitations on archaeolzoological data – taphomony

Archaeozoologists study animal bones encountered in many forms and in various conditions at archaeological sites. Archaeozoological investigations rarely rely on single special finds but rather on the patterns that emerge from analysing many aspects of large assemblages of animal bones, sometimes comprising many thousands of fragments. The bones are typically found damaged and broken. Identification, where possible, is often based on specific morphological details particular to the bones of different species.

Archeozoological assemblages, however, are affected by both natural and cultural transformation processes (Schiffer 1995: 173-189). By the time they appear on the tables of archaeozoologists, they have gone through a series of selective processes that effect which bones survive and in what condition. Recognition of those processes is very important in establishing the power and limitations of this kind of data, just in the same way that it is important to recognize the limitations of written sources which have undergone their own path(s) of selection. This branch of palaeontology and archaeozoology, the critical evaluation of sources, is called taphonomy (Efremov 1940). Taphonomy is the study of post-mortem changes in animal remains. The concept of taphonomy will not be unfamiliar for researchers working with written sources. Who really knows how completely historical sources reflect medieval realities? What was (evidently selectively) entered into the record and how many of the written documents actually survived? Rules of taphonomy apply, in specific ways, to most disciplines concerned with reconstructing the past.

First, certain animals were selected for slaughter or died at a settlement. Those that simply die and are not exploited for their skins or meat will often be dumped and will at most be affected by scavenger activities and how quickly the carcasses were disposed of. Typically in medieval Hungary dog and horse are less likely to have been eaten and thus, more likely to be found as articulated or semi-articulated skeletons on sites. If such animal corpses are deposited off settlement (e. g. on the roadside), their chances of recovery by archaeologists dramatically decrease. This may explain, why only a fraction of camel bones, expected on the basis of the Ottoman Period military records, are actually recovered by archaeologists (Figure 3). Animals killed for their meat and hide tend to be well-represented in excavated assemblages. The slaughtered animals were first selected from a herd. The criteria for selection (e. g. age and sex) depended on whom the animal products were intended for, since wealthier patrons in the Middle Ages were more likely to have access to younger, healthier animals for food. After being slaughtered and skinned, the animal’s carcass would have been divided and distributed depending on who owned the animal, which people or groups had rights to its meat or went through distribution networks among the butchers at major, urban settlements. Next, the body parts would have been further cut up into pot-size pieces depending on local culinary traditions. Cooking and consumption further affect what bones are found and how they are preserved. On the one hand, food processing means that more bones, that is, zoological information were destroyed, but on the other, activities related to butchering and culinary practices leave tell-tale, repetitive signs of traditional carcass treatment which reflect varying customs within and between different socio-economic groups in the Middle Ages. The presence of particular skeletal elements from food processing can also be interpreted by written sources such as contemporary cookbooks. In addition to food-processing, the survival of the bones also depended on how they were thrown away, to what extent were they exposed to natural, post-depositional conditions during fossil diagenesis (Lyman 1994). Charters, account books and images from the same time and region can also be of tremendous help in interpreting patterning in refuse bone accumulations. Unfortunately, it must be added that the final taphonomic factor is all too often the excavating archaeologist, who chooses the location to be uncovered, and makes technical decisions concerning the precision of excavation techniques, methods of documentation and storage. Excavations at medieval sites are all too often centered primarily on architectural structures such as walls, rather than the full range of material culture still available. In addition, techniques of fine recovery, such as screening or water-sieving the excavated material are often ignored. This leads to the size-selective loss of remains from small animals (fish, birds, reptiles, small mammals; Bartosiewicz 1983). Bones of young individuals can also be found only using careful techniques and yet such bones would provide valuable information about herd management strategies and culinary custom.