Medieval Animal Bones

The Various Voices of Medieval Animal Bones

Alice M. Choyke, Kyra Lyublyanovics, László Bartosiewicz (Budapest)

Contents

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Limitations on archaeolzoological data – taphomony

- 3 Primary and secondary products

- 4 Muhi town – archaeozoological data and written sources from the Great Hungarian Plain

- 5 Consumption versus production of animals and animal products

- 6 Domestic and wild

- 7 Detecting religious behavior

- 8 Attributes and symbols

- 9 Conclusions

- 10 References

Introduction

Animals have been woven almost imperceptibly into the complex web of human existence from the very beginning of human history. From the far off times of the Paleolithic past up to the present day, animals have permeated every aspect of our ancestor’s lives and our own. Archaeozoology is the identification, analysis and scientific as well as socio-cultural interpretation of animal remains from archaeological sites. Such zoological finds have been exposed to ancient human activity (animal husbandry, processing etc.). Consequently, archaeological animal bone assemblages are “artifacts” that embody cultural processes. Often the human – animal interaction was purely practical, basically geared toward subsistence. Animals, coming from agricultural production systems were selected for slaughter, their carcasses divided between artisans working in various crafts and the butchers who sold their meat. These assemblages tell archaeozoologists what species were eaten, old the animals were, what they looked like etc. Marks of butchery reflect carcass partitioning both by the butcher and later during food preparation. These steps all involve choices fundamentally dependent on idiosyncratic cultural practices. These tend to be conservative and change only slowly unless radical outside pressure is exerted on food habits. The economically most important domestic animals, sheep (Ovis aries), goat (Capra hircus), cattle (Bos taurus) and pig (Sus domesticus) provided meat and milk for food. Their skins were made into clothing such as tunics and shoes or parts of equipment including straps for harnesses. The production of and trade in these goods formed significant parts of medieval economies. Bones, teeth, antlers and horns were also made into all sorts of utensils and ornaments, widely sold and used throughout every period. Before the advent of mechanization, horse (Equus caballus), donkey (Equus asinus) and mules/hinnies (Equus mulus/hinnus) as well as cattle were used to move people and goods long distances and pull heavy loads in agriculture, construction work and military transport. Draught oxen were widely used during the Middle Ages and much appreciated in heavy-duty work such as tillage and forestry work. Training good ox teams was a lengthy and tedious task, which made them especially valuable (Bartosiewicz et al. 1997). During the 16-17th century Ottoman Turkish occupation of Hungary great numbers of camels (Camelus sp., probably dromedaries), were used in shipping artillery supplies (Bartosiewicz 1996).

Hunting in the Middle Ages was restricted to the nobility but was always maintained as a mark of status and male identity. The most important game animals were red deer (Cervus elaphus) and wild boar (Sus scrofa). From archaeozoological assemblages and contemporaneous images we know that hare (Lepus europaeus) was also hunted, beaver (Castor fiber) and ermine (Mustela erminea), important fur animals, were also important in trade. Of course, all sorts of fish (Pisces), were also key items in the fasting diets throughout Catholic Europe. Even aquatic mammals, beaver and otter (?; Lutra lutra) could form a legitimate part of meals for Lent. Naturally, living with animals so closely, beasts existed for people on a mental level as well. For the elite classes the ownership of special breeds of dogs (Canis familiaris; Figure 1), highly-bred horses and sure-footed saddle mules as well as birds of prey used in falconry (chiefly Accipitridae) represented the closeness of the animal-human connection beyond everyday practicality. Importantly, such animals were also markers of status and prestige.

Conversely, some exotic animals in their strangeness roamed on the darker, more sinister side of people’s imaginations, frequently depicted in scenes of hell and the damned. From very early times, parts of animals were combined to make fantastic beasts also with their recognized qualities and topoi. Such beasts existed vividly in the imagination of medieval people. Perhaps, even if they were not encountered on a daily basis they were still an ever-present part of the culturally acknowledged structure and explanation of the world as it was understood by people in a given community at a given time.

Even relatively straightforward depictions of animals in medieval times display inter-specific mixing of body parts, so that even the well-known species such as horses may be shown with carnivore paws and dogs with hooves. This is in contrast with the Roman world where fantastic animals are depicted combining traits from multiple species but were clearly separated from the animals of everyday life, depicted very prosaically, realistically, as they would be described today in the western world. Finally, animals entered speech as metaphors about the nature of the world. It is on this level that the borderline between what is the nature of a human and what is the nature of an animal becomes fundamentally blurred so that angels have wings and devils cloven hooves or bird claws.

It may look surprising, that the first known osteological reconstruction took place within the context of scholarly research into unicorns. The skeleton of this animal (also depicted in Platina’s 1542 cookbook; Fahrenkamp 1986: 34), was assembled in good faith by Otto von Guericke (1602–1686) from the scattered remains of a mammoth (Mammuthus primigenius) and other extinct ungulates, recovered from a sinkhole near Zeunickenberg, Saxonia (Leibniz 1749; Figure 2). (Von Guericke was acclaimed for his famous 1650 Magdeburg vacuum experiment: two teams of eight horses were unable to pull apart the brass hemispheres whose air content had been sucked out).

Limitations on archaeolzoological data – taphomony

Archaeozoologists study animal bones encountered in many forms and in various conditions at archaeological sites. Archaeozoological investigations rarely rely on single special finds but rather on the patterns that emerge from analysing many aspects of large assemblages of animal bones, sometimes comprising many thousands of fragments. The bones are typically found damaged and broken. Identification, where possible, is often based on specific morphological details particular to the bones of different species.

Archeozoological assemblages, however, are affected by both natural and cultural transformation processes (Schiffer 1995: 173-189). By the time they appear on the tables of archaeozoologists, they have gone through a series of selective processes that effect which bones survive and in what condition. Recognition of those processes is very important in establishing the power and limitations of this kind of data, just in the same way that it is important to recognize the limitations of written sources which have undergone their own path(s) of selection. This branch of palaeontology and archaeozoology, the critical evaluation of sources, is called taphonomy (Efremov 1940). Taphonomy is the study of post-mortem changes in animal remains. The concept of taphonomy will not be unfamiliar for researchers working with written sources. Who really knows how completely historical sources reflect medieval realities? What was (evidently selectively) entered into the record and how many of the written documents actually survived? Rules of taphonomy apply, in specific ways, to most disciplines concerned with reconstructing the past.

First, certain animals were selected for slaughter or died at a settlement. Those that simply die and are not exploited for their skins or meat will often be dumped and will at most be affected by scavenger activities and how quickly the carcasses were disposed of. Typically in medieval Hungary dog and horse are less likely to have been eaten and thus, more likely to be found as articulated or semi-articulated skeletons on sites. If such animal corpses are deposited off settlement (e. g. on the roadside), their chances of recovery by archaeologists dramatically decrease. This may explain, why only a fraction of camel bones, expected on the basis of the Ottoman Period military records, are actually recovered by archaeologists (Figure 3). Animals killed for their meat and hide tend to be well-represented in excavated assemblages. The slaughtered animals were first selected from a herd. The criteria for selection (e. g. age and sex) depended on whom the animal products were intended for, since wealthier patrons in the Middle Ages were more likely to have access to younger, healthier animals for food. After being slaughtered and skinned, the animal’s carcass would have been divided and distributed depending on who owned the animal, which people or groups had rights to its meat or went through distribution networks among the butchers at major, urban settlements. Next, the body parts would have been further cut up into pot-size pieces depending on local culinary traditions. Cooking and consumption further affect what bones are found and how they are preserved. On the one hand, food processing means that more bones, that is, zoological information were destroyed, but on the other, activities related to butchering and culinary practices leave tell-tale, repetitive signs of traditional carcass treatment which reflect varying customs within and between different socio-economic groups in the Middle Ages. The presence of particular skeletal elements from food processing can also be interpreted by written sources such as contemporary cookbooks. In addition to food-processing, the survival of the bones also depended on how they were thrown away, to what extent were they exposed to natural, post-depositional conditions during fossil diagenesis (Lyman 1994). Charters, account books and images from the same time and region can also be of tremendous help in interpreting patterning in refuse bone accumulations. Unfortunately, it must be added that the final taphonomic factor is all too often the excavating archaeologist, who chooses the location to be uncovered, and makes technical decisions concerning the precision of excavation techniques, methods of documentation and storage. Excavations at medieval sites are all too often centered primarily on architectural structures such as walls, rather than the full range of material culture still available. In addition, techniques of fine recovery, such as screening or water-sieving the excavated material are often ignored. This leads to the size-selective loss of remains from small animals (fish, birds, reptiles, small mammals; Bartosiewicz 1983). Bones of young individuals can also be found only using careful techniques and yet such bones would provide valuable information about herd management strategies and culinary custom.

Primary and secondary products

Patterns observed in the faunal assemblages primarily reflect meat consumption, and only indirectly production in terms of herd structure and the broader economic significance of particular animal species. People have always exploited animals for their meat, hide, sinews, bone and horn. These kinds of products require killing the animal and are therefore considered primary products by archaeozoologists. Primary exploitation produces the bone remains that are actually found. Secondary products are those which are renewable because these forms of exploitation do not actually permit killing the animal. Secondary products include, milk and dairy products, wool, manure and animal labor. Animals used this way must be kept alive for a longer time in order to fully exploit their production potential. While the concept of secondary products is associated with domesticates, a special case is represented by shed antler, a wild animal product that can be gathered without harming the animal. Domestic pigs have always been raised primarily for meat. In contrast to unipara domestic ruminants and horse, they have large litters and and a relatively short reproduction cycle. Thus, many of their offspring can be slaughtered young without effecting the survival of the herd. Other domestic animal species tended to be slaughtered after they had outlived their exploitation for secondary products. There are many images showing secondary use, otherwise hardly detectable in the archaeozoological find material. Such iconographic representations include horses being ridden by the elite, donkeys hauling loads and oxen pulling wagons and plows. There are also comments on the worth of these animals in charters and account books as well as many sources referring to their use in long distance trade. The use of individual animals in hard work may lead to pathological deformations, chiefly in the lower limb bones (Bartosiewicz et al, 1997). Sometimes, the archaeological provenance of animal bones, in connection with information from contemporaneous images, provides further insights into the meaning of the faunal assemblage. Thus, horse skeletons buried near structures like stables form high-status households would be reliably interpreted as riding horses giving new meaning as well to the size and body conformation of the skeletons. Many other secondary products from animals cannot be directly inferred from patterning in the bone material because of all the taphonomic processes discussed above. Nevertheless, the age and sex structure of herd animals managed especially for wool and milk (female longevity, fewer males) have long been recognized in the archaeozoological literature (Payne 1975). In other words, a particular herd structure means that certain kinds of animals are more available than others for slaughtering. If such patterns in the faunal material are compared to relevant historical documents concerning what kinds of animals and what products are important in the local economy it should then be possible to build a reliable picture of animal exploitation falling someplace between the often ideal situation represented in the documents and the reality on the ground. This interplay between textual and archaeozoological data will be presented in the following detailed case study.

Muhi town – archaeozoological data and written sources from the Great Hungarian Plain

It is clear that at some points archaeozoolgical data and historical sources support each other and at other points they contradict. These latter dichotomies in the data require explanation which will only be forthcoming after a number of related studies are carried out using similar, multidisciplinary methodologies. The archaeozoological analysis of this material is carried out by the second author of this paper. This brief summary serves to illustrate results as well as analytical problems that have risen during the ongoing archaeozoological and historical evaluation of these finds.

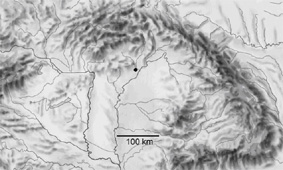

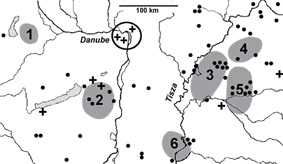

The medieval market town of Muhi was located in the northeastern section of the Great Hungarian Plain, in the foreland of the Northern Hills, near the left bank of the Tisza River. It belonged to the medieval manor of Diósgyőr (Figure 4). Excavations brought to light masses of 13th-16th century animal bones from the area of this town. One of the important features of this work is that relatively few written sources deal with Muhi, making the archaeological information all the more important. On the other hand, the parallel study of the find material and written contemporary sources from the broader region surrounding Muhi itself offers an opportunity to appraise the general versus special relevance of this latter information to the town itself, underrepresented in the documents. The animal remains that have been recovered are of help in pinpointing specific features of the town itself. There is indeed relatively little concerning animal keeping and livestock trade in the written sources that deal with Muhi. This may be in part due to the fact that, to date, relatively little research has been carried out on this topic. It was chiefly the joint works by Péter Tóth and András Kubinyi which exploited archival sources in the region and made many of the sources available. Their research, however, concentrated on the history of the town of Miskolc.

Aside from their work, the comprehensive ethnographic work by Attila Paládi-Kovács (reference) on the animal keeping culture of Hungary contains numerous important references and culture historical data. In spite of these important contributions, however, the information available is sporadic and unreliable. As will be demonstrated here, the chief difficulty is that the analyst is faced with differences in the fundamental nature of archaeological and documentary/historical evidence that are not necessarily complementary to each other. This makes placing any information within a coherent context very difficult. Animal bone measurements used during the archaeozoological study were taken based on a widely accepted standard (von den Driesch 1976).

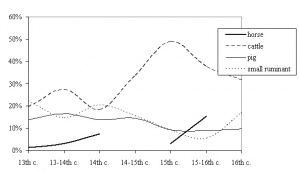

Diachronic trends in the representation of domestic animals in the archaeozoological assemblage of Muhi are summarized in Figure 5. Coincidences and discrepancies between the picture emerging from the written record and trends shown in this graph will be briefly reviewed here. The first question encountered during the study of historical sources is, to what extent the town of Muhi participated in live cattle trade that gained momentum in Hungary after the 15th century? The geographical location would have been perfect for this purpose, since Muhi was an important market center in the vicinity of Miskolc town. Muhi became a market town at the end of the 13th century and organized frequented weekly markets from the 14th century onwards (Tóth 1994: 115; Borovszky 1909: 48; Bessenyei 1997: 208-209; Szendrei 1911: III: 251). Significant cattle drives toward the town of Pusztapécs (Auspitz/Hustopeče) in southern Moravia, through Nagyszombat (Trnava, present-day Slovakia) passed near Muhi. In addition, livestock were also driven west from Debrecen toward the Vác ferry across the Danube within this region.

The types of animal husbandry and herd sizes at individual farms, however, are difficult to characterize. Local cattle traders also participated in buying up and driving livestock abroad, in cooperation with their fellow traders on the Great Hungarian Plain (to the southeast) and in the hilly areas to the north in present-day Slovakia (Tóth and Kubinyi eds. 1996, II: 345). In addition to primary documents concerning livestock trade, the increasing quantity and significance of hay production in the area may be considered an indirect evidence of intensifying cattle trade (Tóth and Kubinyi eds. 1996, II: 178-179). These documents are especially valuable, since they indicate a change that may also be followed in the archaeological material. Possibly with the prosperity coming from the cattle trade, the bones of this animal become more frequent in the deposits of local food refuse as well. In addition, one may expect a change in the types of animals that includes an increase in average size and homogenization of the physical types of animals being produced (phenotype). Ultimately, it would be expected that larger, so-called primigenius type animals became dominant through time leading to the gradual emergence of the Hungarian Grey breed in the following centuries (Makkai 1971: 488-489). In this early time period however, it is not possible to really speak of breeds but rather regional types.

The percentage distribution of the 4404 animal bones identified and studied so far shows that cattle remained dominant throughout the studied period. A peak is evident in the 15th century (48.9%), while deposits dated to the 15th-16th and 16th centuries show some decline in the consumption of beef (37.6 and 31.7% respectively) at Muhi. These proportions, however, certainly reflect the minimum consumption, since most of the bone fragments from “large mammals” that could not be identified to species also probably originate from cattle (horse bones contributed only very little to food remains in medieval Hungary).

Appraising the homogeneity and individual size of these animals is more difficult given the present state of the research. The archaeozoological material is very fragmented, therefore only a few complete metapodium bones were available for the estimation of withers height. Never the less, as much as it may be judged from the size of the fragments that have been measured to date, they represent a small bodied brachyceros, short-horned type of cattle. This is not only characteristic of the material from early, 13th century deposits, but also in the later 15th-16th century material, and is consonant with contemporaneous iconographic evidence (Figure 6). The situation is further complicated by the possibility that in the Muhi area, far from the terminal markets in Austria and Southern Germany, stocks bought from all over the Great Hungarian Plain may still have been more heterogeneous than would be expected on the basis of coeval descriptions from German speaking areas. One should not forget that archaeological finds represent food remains. It is possible that on road stations, such as the market at Muhi, cattle traders sold the meager looking, less fit animals for culling. This theory, however, will have to be supported by a greater number of horn cores and skull fragments waiting to be identified during subsequent research.

In any case, it is noteworthy, that destruction resulting from the expansion of the Ottoman Turkish Empire annihilated only two settlements in the area, Muhi and Petri. This falls in line with the theory that Ottoman attacks first damaged branches of economy that had been vital for the town’s survival. Among others things, Muhi was a well known center of cereal production. Turkish incursions must have posed a direct threat to peaceful land cultivation. In addition, it must also have become increasingly difficult to organize markets. There is a widely held idea that inhabitants in the areas exposed to Turkish invasions increasingly abandoned traditional land cultivation and turned to more flexible forms of range farming. Livestock could be easily mobilized in the case of emergency and could also be sold at almost any time. The deterioration of cattle exports coincides with the depopulation of Muhi town. At the same time, according to written sources, cattle trading peaked in Vác and at other Danube crossings in the late 16th century Ottoman Turkish Period (Bartosiewicz 1997-1998). In 1563 the number of cattle recorded at Vác reached over 6000 animals on a single day in September (Bartosiewicz 1995: 85, Fig. 54). In the same year, when agents of the Hungarian Chamber appraised the income of the Diósgyőr Manor, they made special note of the manor’s great potential represented by trading in animal products (Tóth and Kubinyi eds. 1996, II: 176, 182, 184). This may indicate that a significant livestock surplus must have been kept in the villages and towns of the region as required by the daily need of their inhabitants. Meanwhile, it seems that Muhi had already ceased to exist! The percentual contribution of cattle bone to faunal assemblages from archaeological sites located near the cattle trading routes in western Hungary is over 60% (Bartosiewicz 2002: 90, Fig. 2), well exceeding that found at Muhi even when it was at the peak of its cattle trade. This may be interpreted as reflecting a general increase in the importance of cattle at focal points in the cattle trade by the 16th-17th century Ottoman Turkish Period. It is the number of farms specialized in sheep keeping increased during the 16th century (Paládi-Kovács 1993: 149). Smaller groups of Vlach shepherds settled in certain, depopulated parts of the Great Hungarian Plain as early as the 15th century and brought their special herd stocks with them. A good example of this trend could be observed in the village of Mezőkeresztes, in the proximity of Muhi. Written sources reveal that Vlach shepherds had special grazing rights on both banks of the Tisza River, and practiced large-scale sheep husbandry even at the end of the 16th century. In 1579, for example, the 22 heads of the families living there paid decimal taxes in the form of 212 sheep (Borovszky 1909: 151). Tax records from the 16th century also show a concentration of sheep stocks in other areas of the Great Hungarian Plain. This may be indicative of the specialization of the livestock owners. Individual households would not have kept more than one or two sheep or goat. Although sheep were also bred on the majority of manorial farms in Northeastern Hungary, peasant farmers and larger enterprises played an even more decisive roles compared to the manors. Grazing large herds of sheep near Muhi would explain the great supply of sheep at the markets of Muhi, often referred to in written documents. István N. Kiss studied tax duties paid in lambs in Heves, Borsod, Bihar and Szabolcs counties. His research has shown that, especially in the regions of Heves and Borsod counties located near the Tisza river, sheep husbandry was extremely important. Regional sheep stocks may have been close to 30,000 animals as has been convincingly illustrated using by N. Kiss (1960). It is likely that these nearby herds also supplied sheep to the markets of Muhi. In light of this results derived from written sources it is surprising that the contribution of sheep and goat bones to the archaeological assemblage at Muhi was relatively low. In the archaeozoological material, the contribution of small ruminants (predominantly sheep) is 20.4% in the 14th century features. This proportion, however, declines to 15.6% by the turn of the 14th-15th centuries and reaches only 9.3% by the 15th century. An increase may be observed in the 16th century sub-assemblage, up to 17%. Curiously enough, the all time low shown in these data coincides with the time period that is described as the time of expanding sheep herding in written sources. This apparent contradiction is yet another warning, that archaeozoological finds directly characterize meat consumption, rather than animal husbandry. In the case of sheep, a domesticate animal exploited for secondary products such as wool and milk, the intensive culling of animals for meat was not in the owners’ long term interest. Several new breeds of sheep developed in the Carpathian Basin during the 15th-17th centuries (Gaál 1966: 189; Makkai 1957: 27). Unfortunately, the identification of these forms is practically impossible on the basis of osteological remains alone, unless horn cores of characteristic shape are encountered, as would be the case with Racka sheep with its upward pointing, corkscrew-like horns. The first appearance of this breed, post dates the period under discussion here both in the archaeological material (Bartosiewicz 1995: 166, Plate 6) and in the iconographic record (Figure 7).

The northern-northeastern margin of the Great Hungarian Plain was an important pig keeping region as well. On the basis of written sources, however, it was Bihar, rather than Borsod county, where these pigs were important. There are written references to acorn-based pig ranging in the oak forests of the Bükk hills. This means that fattening actually began once the acorns fell and lasted until Christmas. Winter fattening was also based on acorn, gathered during the fall. Forests belonged to the manor’s owner, who therefore collected a decimal tax paid in pigs (Tóth and Kubinyi eds. 1996 II: 188). From the 14th century onwards, pigs were also fed on fodder made from grain and milling refuse. A system developed in which pigs to be fattened were kept near the mill, in the care of millers. However, only a relatively small number of pigs were kept this way (Belényssy 1956: 28; Gaál 1966: 121).

Our hypothesis was that pig keeping was not practiced on a commercial basis, but rather served local demands for meat. Never the less, the proportion of pig bones remains at a steady 12-13% in the archaeological faunal material; At the turn of the 13th-14th centuries it surpasses the contribution of small ruminant bones and remains largely at the same level during the Ottoman Turkish Period. This latter phenomenon contradicts the widely held idea that under the influence of Islamic food customs pig would have lost significance after the Turkish conquest. Demand may have somewhat decreased although Turkish authorities taxed pig keeping, actually maintaining what was formerly collected as pig decimal tax. As for trying to reconstruct the type of pigs kept, this work is made difficult by the fact that, as is usual with meat purpose stock, the remains of young pigs dominate in the excavated material. Mature body dimensions and morphological characters are only poorly expressed in the bones of young individuals. There were hardly any measurable pig bones in the archaeozoological assemblage. The majority of fragments, however, seem to indicate that these were leggy but small type pigs with a primitive character, possibly also owing to spontaneous crossings with wild pig (Bökönyi 1993: 102). A special type of medieval pig with broad jaws described by Bökönyi (1963: 383; and 1974: 223) has not yet been encountered in the faunal assemblage from Muhi. General experience shows that reconstructing late medieval and Early Modern Age horse keeping is very difficult on the basis of bone remains, since the remains of horse are rarely encountered in the food refuse. It is likely however, that the high levels of horse breeding already recorded in Borsod County in the 10th-13th century Árpád Period continued supplying exported animals in the county’s broader environment. Exports to Poland were also recorded. There was a considerable market demand represented by the local military during the Ottoman Turkish Period. Landowners in Diósgyőr also contributed to the horse trade (Tóth and Kubinyi 1996, I: 274-275; II: 183). Horse, a valuable animal, is well represented in the written sources. However, since its flesh was not supposed to be consumed in Christian times, horse bones are relatively rare in ordinary settlement refuse. This Ottoman Period boom in horse trading also had its dark side. Horses were regularly taken as war booty by marauding Turkish soldiers (Paládi-Kovács 1993: 17). The proportion of horse bones is surprisingly high in the archaeozoological material from several periods at Muhi. Among the 14th century finds the contribution of horse bones was 7.5%, which increased to 15% by the 15th-16th century (!). However, it is difficult to contextualize this information. The estimation of minimum number of individuals (based on the frequency of the most commonly occurring skeletal element) would not make a lot of sense, since almost all parts of the skeleton are present. On the other hand, all the horse bone that were found were so scattered, that it is impossible to tell whether any of them belonged to the same individual in a physical sense. Butchering marks, offering evidence of defleshing, were not found on these bones: horse remains commonly occur in the form of such sporadic and isolated finds at medieval sites, representing carcasses which have been scattered by scavengers rather than broken up through food processing. Horses were certainly eaten at the time of the 9th century Hungarian Conquest, and this custom was not completely abandoned even after Christianity had been adopted (Matolcsi 1982: 252-253). However, the horse finds from Muhi are not relevant to this problem. Although cutmarks occur on the lower, distal bones of the extremities, such marks are widely regarded as evidence of skinning. Bone fragmentation cannot be interpreted as the result of meat processing, since such damage to the bone may be caused by a number of taphonomic factors. The only convincing evidence of horse flesh consumption would be the presence of numerous butchered horse bones in the material still remaining to be studied. The complete horse bones from Muhi are indicative of a relatively homogeneous form. They look like gracile, slender-legged animals, often referred to as of “eastern” character. This general picture is somewhat colored by the variability in estimated withers heights. Small individuals with withers heights of ca. 130 cm, as well as large horses measuring approximately 150 cm were found in similar proportions, both in the earlier 13th-14th and later, 15th-16th century material. Naturally, these sporadic estimates, based on single bones, do not justify speaking of two distinct types, they indicate that one should revise the generally held opinion that medieval horse stocks consisted of small, primitive forms (Paládi-Kovács 1993: 97-98). Some of the bones showed pathological lesions. Most of these are deformations that may be explained by overworking. It is worth mentioning in this regard that horses were used in plowing near the lowland settlements of Borsod County, such as Muhi..

Consumption versus production of animals and animal products

As is shown by this case study, although the interpretation of animal remains from archaeological sites is often geared toward the understanding of animal keeping and animal husbandry in a broader sense, it must be understood that these fundamental modes of production have been reconstructed from consumption refuse, left behind at the site in the form of animal bones. The original production context is, to some extent, represented in the nature of the site they come from (for example urban, rural, elite or peasant, civilian or military) and the broader geographical environment of the settlement. Within sites, the physical context is also important. Animal remains may have been scattered in open middens, deposited in abandoned wells, pits. They may also have been associated with special structures such as houses, monastic dwellings, shops and elite households in castles and palaces. Importantly, understanding the context for bones can be further improved by a variety of outside sources, both written and pictorial, providing information about the function of the settlement and the nature of economic activities carried out there. At simple rural sites, where animals were brought directly into settlements for slaughter, some of the stages described above were skipped. At the late antique site of Aquincum in Budapest bones from the center of the Roman town had clearly passed through several filtering processes, and above all professional butcher shops. The Celtic Roman villages on the outskirts of bone display a totally different picture. Animals were brought directly into the village to be slaughtered and divided up among families. Methods of dividing the carcass and breaking bones remained unchanged from that of their pre-Roman Celtic ancestors (Choyke 2004). Even in this case, however, it remains very difficult to discern the herd structure behind the food consumption patterns from the animal bones recovered from the two sorts of kitchen refuse.

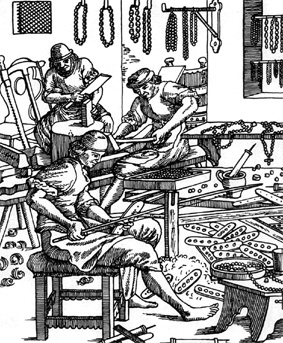

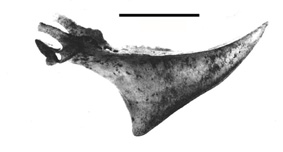

Leather production leaves accumulations of bones from the lower limbs and skull often left behind in the hides because it makes it easier to handle and stretch them. There are a number of images showing this technical solution (Figure 8). Closely associated with tanners were people working in glue. Animal foot bones especially were broken up to help extract the collagen from them. On the skulls, the osseous horn cores often have cut marks around their bases where the horn sheath was separated from the bone below it (Figure 9). Bones in skins and with horn sheaths in place were often directly taken to workshops from urban slaughterhouses. The Late Roman town of Aquincum has a number of bone accumulations comprised mostly of horncores and lower limb bones which have been ascribed to such leather and horn processing workshops (Choyke 2004). Similar bone accumulations can be expected from medieval Buda and Pest as well.

Bone and antler working are medieval crafts about which not much is written although these were widely used raw materials throughout the Middle Ages. Bone workers in medieval Buda seem to have been associated with wood workers because both worked on lathes (Kovács 2005). There are no written records about bone working in Buda although mention in sources is made of a man named Chontws (‘csontas’ in Hungarian means boney’) who was associated with people from the Turners’ guild (Kovács 2005: 311). Refuse from the manufacture of bone objects resulted refuse characteristic of lathe-working so that the historical sources and the archaeological material complement each other (Figure 10). Furthermore workshop debris with evidence of sawing and rings of bones produced when producing rods of bone meant for further working remain signposts for bone workshops (for example see Gróf and Gróh 2001: 282).

Antler from red deer (Cervus elaphus) is an important raw material. More resilient and denser than bone, it is ideal for tools and ornaments which are subject to shocks. In the Middle Ages it is likely that most antler was gathered. Stags shed their antlers in the early spring within particular territories. It was important to gather the antler immediately as it deteriorated if left lying on the ground. This suggests that antler-gathering must have been an intensive, seasonal activity. There must also have existed some form of exchange between urban craftspeople and the population living in the countryside (MacGregor 1985, 36-37). Antler was undoubtedly stockpiled and indeed pits are sometimes found on sites from many periods containing a few red deer antler racks for storage throughout the year. The species chosen and available for working depended on manufacturing traditions in the particular place and time. It also seems evident that bone was often worked by artisans such as knife-makers. Again, approximately locating metal workshops on the basis of written sources combined with the recognition of refuse from bone manufacture from archaeological sites in their vicinity offers a fuller picture of manufacturing organization(s) in a particular period.

Domestic and wild

By the Middle Ages, domestic animals provided the overwhelming majority of the meat consumed. Even food refuse from high status sites shows that eating meat was the exception rather than the rule. Some of the animals killed, however, came from the wilderness surrounding human settlements. Animals were typically hunted by privileged, landed classes with special rights during the whole of this long period although poaching must have also been sporadically practiced by all classes. Furthermore, as agricultural territories expanded, many of the wild animals survived in shrinking habitats or in artificial ‘forest’ reserves set up by the nobility specifically for sport hunting. Trophies must have been held in high esteem, especially if they represented fearsome animals and originated from far away territories. A skull fragment with the pair of upper canine teeth of an unusually large medieval leopard, found at the queen’s town in Segesd (Bartosiewicz 2001), must have originated from at least as far as Transcaucasia, since this animal did not live anywhere closer to Europe. This bone may have been carried to Hungary as the decorative element in a pelt used as a rug or as high status attire. This is shown by the high polish on the back side of the bone, carefully cut off at the animal’s nose (Figure 11).

Fishing was also of critical importance in the economic life of Europe because fish was so important in religious diets. Fish were grown in extensive fish pond systems and even traded (salted and dried) across the continent and much has been written about this trade both in historical and archaeozoological literature (for example Hoffman 1997; Van Neer and Ervynck 2004). Masses of small fish must have been very important in the diet along rivers, such remains, however, are difficult to find without water-sieving. In great rivers such as the Danube, large sturgeon (Acipenseridae) and catfish (Silurus glanis) were caught. These fish reach huge sizes so their bones are more likely to be found, even where the excavation techniques are limited to hand-collection. In addition, there exist excellent images and written documents concerning fishing weirs along various points on the Danube (Khin 1958). Such a structure and the relevant historical landscape in the Iron Gates Gorge are shown in an excellent picture published by Marsigli (1726), an Italian military engineer and polyhistorian, who traveled along the Danube recording his experiences (Bartosiewicz and Bonsall 2004: fig. 8). Consumption of certain luxury animals certainly signaled status during the medieval period. The consumption of immature animals has already been mentioned but it is also clear that exotic or unusual animals also appeared on the tables of the upper classes or aspiring upper classes as a sign of their otherness from the peasantry (Ervynck et al 2003). One of the specialities newly introduced to Hungary was turkey during the 16th century (Figure 12; Bartosiewicz 1997). The earliest known bone remains of this New World bird are usually found in urban deposits and castles (Bartosiewicz 1995).

Detecting religious behavior

Because many medieval archaeological sites are complex they undergo continuous re-modeling. This means that it is extremely rare to find deposits in primary position. In addition to floor deposits, storage pits converted to refuse pits, wells and cisterns offer some chance to find animal remains possibly related to food proscription. There are increasing numbers of studies of medieval materials where it has proved possible to recognize food practices in the archaeozoological material, for example where turtles or aquatic mammals such as otter or beaver were substituted for fish on fast days in the diet of two religious orders in Italy (De Grossi Mazzorin and Minniti 1999). In Hungary, 12 m deep well was excavated between 1999 and 2000 at Teleki Palace in the Buda castle yielded an elaborate piece of textile, shoes and other rare organic materials, preserved under anærobic circumstances. In addition, a fragment of a wooden plate decorated with a Star of David and a fragment of glass with Hebrew writing on it were discovered in the lower layers. Because of all these special finds, the well was excavated with unusual care, all the deposits being washed, screened and carefully picked through. It was known from documents that the first Jewish population was located somewhere this area in the 13th-14th century although nothing else was known about it. It was hoped that the character of the archaeozoological material would support locating the quarters of this first Jewish population in the area around the well. It was discovered that with the exception of one bone fragment no pig bone appeared in the lower levels at the well (Daróczi-Szabó 2004: 252-243). Jewish dietary law prohibits use of the hind legs of animals like cattle or sheep. At this site there were fewer hind leg bones in the lower levels. Their presence may indicate that these Jews permitted eating meat from this limbs if the sciatic nerve was properly removed which sheds interesting light on the nature of the strict observance practiced by this medieval Jewish community (Daróczi-Szabó 2004: 261). Meanwhile, bones of catfish, a species with no scales, as well as those of sturgeon, another fish avoided by Jews for the same reason were only found in the upper levels from a time when the Jewish population had been expelled from the area (Bartosiewicz 2003a). Deposits associated with neighborhoods of mixed religion or less observant Islamic inhabitants during the 150 years of Ottoman Turkish occupation of the Carpathian Basin show a much less clear cut avoidance of pork (Bartosiewicz and Gál 2004) something also observed at Muhi cited in this paper. Although there was a general decline in pig consumption during the Ottoman Period in Hungary (Bartosiewicz 2003b), prohibition against pork is evident only in the exclusive, high status habitation of the Pasha’s Palace in Buda (Bökönyi 1974).

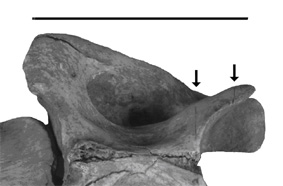

Religious behaviour is not only represented in the presence and absence of certain animal species in the diet. A special example is also worth mentioning here from the 15th century, Inca Period site of Incarracay in Bolívia (Bartosiewicz 1999). Fine transversal cutmarks were discovered on the ventral surface of a small camelid (Lama c. f. pacos) atlas, the vertebra adjacent to the skull (Figure 13). This damage may be alternatively explained by either slaughtering or patterned carcass partitioning, that is, post mortem decapitation. Since these cuts occur on the anterior edge of the cranial articular surface, stricto sensu, they may have been caused by the latter, according to the criteria established by Gilbert (1988: 85, Fig. 5, Pl. XIV/1-4). Never-the-less a neck vertebra damaged by any cutmarks may be of religious significance at this particular site. In pre-conquest Perú, sacrificial lamas were killed by tearing their hearts out. In 1615, the chronicler Poma de Ayala ([1990]: 160) even warns: “Do not kill it this way, but do it like the Christians nowadays, by cutting the ram’s neck...”. That is, slitting the animal’s neck was considered a distinctly non-traditional, culturally idiosyncratic, that is, Christian mode of slaughter.

Attributes and symbols

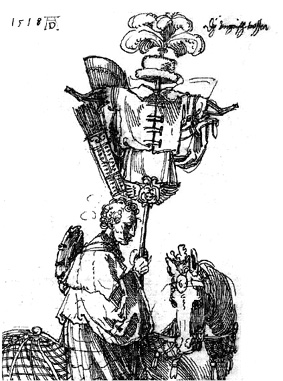

In parallel, humans observing animal behavior and interpreting it in terms of human social terms began attributing human characteristics to these creatures. This has helped shape our constantly evolving attitudes toward the world, with animals forming an integral part of it. Animals conceived as metaphors are not physically tangible in the same way as the bone remains of those animals. Neither do the bones themselves, ultimately the results of consumption, shed much light on the roles of animals in all aspects of social, economic, political or religious affairs. From the archaeozoologist’s point of view external evidence must be considered to be able integrate zoological information within a broader picture. A hat decorated with crane feathers (as well as a reflex bow), are shown in Dürer’s sketch made for the triumphal march of Emperor Maximilian, entitled the “Hungarian trophy” (Figure 14). Both the historical and ethnographic record shows that crane feathers indeed had special ornamental importance in Hungary (Gunda 1979). The bones of this bird also occur relatively frequently in archaeozoological assemblages (Figure 15, Jánnossy 1985). Although no evidence of feathers survives in the archaeological record, combining toponyms related to crane, ethnographically known regions of crane taming and the find locations in the same map shows a concentration of crane bones (encircled in Figure 15) in the hilly region of the Danube Bend gorge, relatively far away from the areas marked by linguistic ethnographic evidence that would logically define ancient crane habitats. This indirectly shows that cranes, also known to have been kept as pets in noble households, were exploited away from their preferred environments (Bartosiewicz in press).

Together with common myths and stories about human and animal interactions animal images were used to instruct and associated with protective qualities appearing in the form of amulets. Animals and their products could reflect prestige either because of their special qualities as a breed or exotic origins and form. Hunting large game was frequently a test of manhood. Rarely, the skulls of the large animals show up in contexts suggesting their use as trophies displayed on walls. There are also examples where skulls of horses were hung up on buildings for apothropaic purposes. In the correct context such skulls may also be recognized in archaeological materials. At the beginning of the Middle Ages in Europe, horses in particular were still placed in the graves of the Avars people as complete animals. At the time of the 9th-10th century Hungarian Conquest, pre-Christian burials contained only the skull and lower limb bones of horses, suggesting the bones were attached to a hide. In any case, these modes of burial may be regarded as the pars pro toto representation of the entire animal.

After the onset of Christianity, animals continued appear as attributes for saints and apostles. As symbols, they still were used to represent visual and textual shorthand for basic human qualities ranging widely from modesty to jealousy. The line between different animal species as well as humans between and animals was often delightfully and uninhibitedly blurred in the medieval view of the world. Fantastic and grotesque creatures were just as real and important in daily life as the cattle and pigs living side by side with the people who relied on them for survival. Specific cultural attitudes, the qualities attributed to animals, have a direct feedback on which animals were preferred for exploitation in a given place and time and how they were used. Even today, it affects how animal species are used, under what circumstances. These qualities, in turn, have ultimately affected which bones end up in the archaeozoologist’s laboratory.

Conclusions

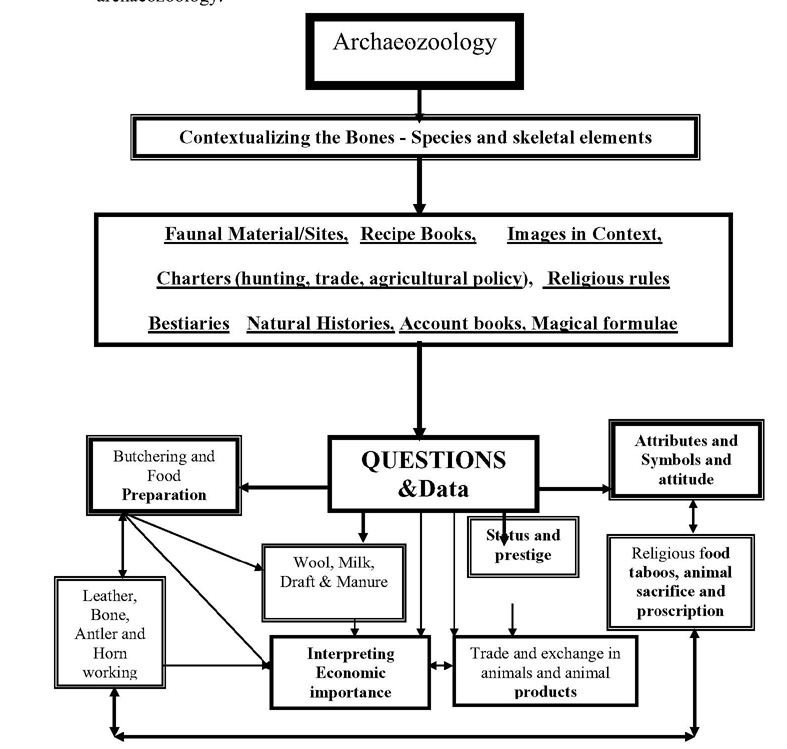

The past history of human-animal connections is ultimately about behavior in a myriad of inter-related natural and cultural contexts, revealed in bits and pieces from a variety of sources. Interdisciplinary approaches to historical problems provide a form of checks on different kinds of sources as well as adding new kinds of data. It goes without saying that recognition and interpretation of special patterns in archaeozoological assemblages is heavily contingent on use of contemporaneous written sources and images (Figure 16). Attempts to move beyond calories to interpreting bones in light of the local economy as well as social organization and affiliation is a growing trend in archeozoology (Van Neer and Ervynck 1996; 2004; Ervynck 2004; Galik and Kunst 2004). Multidisciplinarity, that is, the parallel analysis of written and iconographic sources is an indispensable contribution to medieval archaeozoology.

References

Bartosiewicz, L. 1983. A régészeti feltárás finomításának lehetőségei. Régészeti Füzetek, 2: 37-54.

Bartosiewicz, L. 1995. Animals in the urban landscape in the wake of the Middle Ages.Tempus Reparatum, Oxford.

Bartosiewicz, L. 1996. Camels in Antiquity: The Hungarian connection. Antiquity, 70/268: 447-453.

Bartosiewicz, L. 1997. A Székesfehérvár Bestiary: Animal bones from the excavations of the medieval city wall. Alba Regia XXVI, Székesfehérvár: 133-167.

Bartosiewicz, L. 1997-1998. Animal exploitation in Turkish Period Hungary. OTIVM 5-6: 36-49.

Bartosiewicz, L. 1999. Animal bones from the Cochabamba Valley, Bolivia. In J. Gyarmati and A. Varga eds.: The Chacaras of War. An Inka site estate in the Cochabamba Valley, Bolivia. Museum of Ethnography, Budapest: 101-109.

Bartosiewicz, L. 2001. A leopard (Panthera pardus L. 1758) find from the late Middle Ages in Hungary. In H. Buitenhuis–W. Prummel eds.: Animals and Man in the Past. ARC-Publicatie 41, Groningen, the Netherlands: 151-160.

Bartosiewicz, L. 2002. A török kori Bajcsavár állatai (Animals of Turkish Period Bajcsavár). In Gy. Kovács ed.: Weitschawar/Bajcsa-Vár. Zala Megyei Múzeumok Igazgatósága: Zalaegerszeg: 89-100.

Bartosiewicz, L. 2003a. Eat not this fish – a matter of scaling. In A. F. Guzmán, O. J. Polaco–F. J. Aguilar eds.: Presencia de la arqueoictiología en México. Conaculta–INAH, México D. F.: 19-26.

Bartosiewicz, L. 2003b. A háziállatok régészete (The archaeology of domestic animals). In Zs. Visy ed. Magyar régészet az ezredfordulón (Hungarian Archaeology at the Millennium). Nemzeti Kulturális Örökség Minisztériuma, Budapest: 60-64.

Bartosiewicz, L. in press. Crane: food, pet and symbol. In J. Peters ed.: Proceedings of the 5th meeting of the ICAZ Bird Working Group. Documenta Archaeobiologica, München: 257-268.

Bartosiewicz, L. and Bonsall, C. 2004. Prehistoric Fishing along the Danube. Antaeus 27: 253-272.

Bartosiewicz, L. and Gál, E. 2004. Ottoman Period Animal Exploitation in Hungary. In I. Gerelyes and Gy. Kovács eds.: Archeology of the Ottoman Period in Hungary. Opuscula Hungarica III. Magyar Nemzeti Múzeum, Budapest: 365-376.

Bartosiewicz, L.,Van Neer, W. and Lentacker, A. 1997. Draught cattle: their osteological identification and history. Tervuren, Koninklijk Museum voor Midden-Afrika, Annalen, Zoologische Wetenschappen Vol. 281, Tervuren.

Belényessy, M. 1956. Az állattartás a XIV. században Magyarországon (Animal Keeping in XIV century Hungary). Néprajzi Értesítő Vol. XXXVII: 23–59.

Bessenyei, J. 1997. Diósgyőr vára és uradalma a XVI. sz.-ban (The castle and ruler of Diósgyőr in the XVI century). Források: Miskolc.

Bökönyi, S. 1963. Die Wirbeltierfauna der Ausgrabungen in Zalavár. In Á Sós and S. Bökönyi: Zalavár. Arch. Hung. N.S., XLI, 313-386, Budapest.

Bökönyi, S. 1974. History of Domestic Mammals in Central and Eastern Europe. (Akadémiai Kiadó: Budapest).

Bökönyi, S. 1993. The beginnings of conscious animal breeding in Hungary: the biological, written and artistic evidences. In Durand, R. (ed.): L’homme, l’animal et l’environnement du Moyen Âge au XVIIIe siècle. Enquêtes et Documents 19, Nantes.

Borovszky, S. 1909. Borsod vármegye története a legrégibb időktől a jelenkorig (The history of Borsod county from earliest times to the present). In A vármegye története az őskortól a szatmári békéig (The history of the Counties from Prehistoric Times to the Peace of Szatmár). Budapest.

Choyke, A.M. 2003. Animals and Roman Lifeways in Aquincum. In P. Zsidi ed.: Forschungen in Aquincum 1969-2002. Aquincum Nostrum II/2: Budapest, 210-232. Daróczi-Szabó, L. 2004. Animals bones as indicators of kosher food refuse from 14th c AD Buda, Hungary. In S. Jones O’Day, W. Van Neer and A. Ervynck, Behavior Behind Bones. The Zooarchaeology of Ritual, Religion, Status and Identity. (Oxbow books: Oxford), pp. 252-262.

De Grossi Mazzorin, J. and Minniti, C.1999. Diet and religious practices: the example of two monastic orders in Rome between the XVIth and XVIIth centuries. Anthroopzoologia Vol. 30, pp. 65-77.

Driesch, A. von den 1976. A Guide to the Measurements of Animal Bones from Archaeological Sites. Peabody Museum Bulletin Vol.1. (Peabody Museum Press: Cambridge, Massachusetts).

Efremov, I. A., 1940. Taphonomy: a new branch of paleontology. Pan-American Geologist 74, pp.81–93.

Ervynck, A., Van Neer, W. Hüster-Plogmann, H. and Schibler, J. 2003. Beyond affluence: the zooarchaeology of luxury. In W. Van Neer (ed.) Luxury Foods. World Archaeology Vol. 34/3: 428-441.

Fahrenkamp, J. 1986. Wie man eyn teutsches Mannsbild bey Kräfften hält. München, Orbis Verlag.

Gaál, L. 1966. A magyar állattenyésztés múltja (The Past of Hungarian Animal Breeding). Akadémiai Kiadó: Budapest.

Galik, A. and Kunst, G.K. 2004. Dietary habits of a monastic community as indicated by animal bone remains from Early Modern Age in Austria. In S. O’Day, W. Van Neer and A. Ervynck (eds.) Behavior Behind bones: the zooarchaeology of ritual, religion, status and identity, Oxbow books: Oxford, 224-232.

Gilbert, A. S., 1988. Zooarchaeological observations on the slaughterhouse of Meketre. The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 74: 69-89.

Gróf, P. and Gróh, D. 2001. The remains of medieval bone carvings from Visegrád. In A. Choyke and L. Bartosiewicz (eds.), Crafting Bone: Skeletal Technologies through Time and Space, BAR International Series 937, Archeopress: Oxford, 281-285.

Gunda, B. 1979. Die Jagd und Domestikation des Kranichs bei den Ungarn. In B. Gunda ed.: Ethnographica Carpatho-Balkanica. Akadémiai Kiadó, Budapest: 89-114.

Hoffmann, R. C. 1997. Fisher’s Craft and Lettered Art: Tracts on Fishing from the End of the Middle Ages. University of Toronto Press: Toronto.

Jánossy, D. 1985. Wildvogelreste aus archäologischen Grabungen in Ungarn (Neolithicum bis Mittelalter). Fragmenta Mineralogica et Paleontologica 12, 67-103.

Khin, A. 1957. A magyar vizák története (The history of Hungarian sturgeons). Mezőgazdasági Múzeum Füzetei 2: Budapest.

Kiesewalter, L. 1888. Skelettmessungen am Pferde. Dissertation, Leipzig.

Kovács, E. 2005. Remains of the bone working in medieval Buda. In H. Luik, A. Choyke, C. Batey and L. Lõugas (eds.), From Hooves to Horns from Mollusc to Mammoth, Muinasaja Teadus 15, Tallinn, 309-316.

Leibniz, G.W. 1749. Protogaea oder Abhandlung von der ersten Gestalt der Erde und den Spuren der Historie in den Denkmalen der Natur. Leipzig und Hof, Herausgegeben von Christian Ludwig Scheid.

Lyman, R.L. 1994. Vertebrate Taphonomy. Cambridge Manuals in Archaeology, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

MacGregor, A. 1985. Bone, Antler, Ivory and Horn: the Technology of Skeletal Materials since the Roman Period, Croom Helm, London.

Makkai, L. 1957. Paraszti és majorsági mezőgazdasági termelés a XVII. Században (Peasant and manorial agricultural production in the XVII century). Agrártörténeti Tanulmányok Vol. 2. Gödöllő–Budapest.

Makkai, L. 1971. Der ungarischen Viehhandel 1550-1650. In I. Bog (ed.): Der Aussenhandel Ostmitteleuropas 1450-1650, Böhlau Verlag: Wien.

Marsigli, L. F. 1726. Danubius Pannonico-Mysicus. Vol. VI. Amsterdam – The Hague.

Matolcsi, J. 1982. Állattartás őseink korában (Animal Keeping in the Time of our Ancestors). Gondolat: Budapest.

Paládi-Kovács, A. 1993. A magyarországi állattartókultúra korszakai (Periods of Hungarian Animal Keeping Culture). MTA Néprajzi Kutatóintézet: Budapest.

Payne, S. 1973 Kill-off patterns in sheep and goats: the mandibles from Aşvan Kale. Anatolian Studies 23: 281-303.

Poma de Ayala, F. G. [1990]. Perui képes krónika (El primer nueva crónica y buen gobierno). Gondolat, Budapest.

Schiffer, M.B. 1995. Behavioral Archaeology: First Principals. University of Utah Press: Salt Lake City.

Szendrei, J. 1911. Miskolcz Város Története és Egyetemes Helyirata (The History and Topography of the Town of Miskolc) Vol. III.

Tóth, P. 1994. Szempontok a borsodi mezõvárosok középkori és kora újkori történetének vizsgálatához (Points of view on the analysis of the medieval and Early Modern history of market-towns in Borsod country). Studia Miskolciensia Vol. 1: 113-125.

Tóth, P. – Kubinyi, A. (eds.) 1996. Miskolc története. I-II. Miskolc: Borsod-Abaúj-Zemplén Megyei Levéltár (The History of Miskolc, Vols. I-II. Miskolc: County Archives of Borsod-Abaúj-Zemplén County) – Herman Ottó Múzeum.

Van Neer, W. and Ervynck, A. 2004. Remains of traded fish in archaeological sites: indicators of status, or bulk food. In S. O’Day, W. Van Neer and A. Ervynck (eds.) Behavior Behind bones: the zooarchaeology of ritual, religion, status and identity, Oxbow books: Oxford, 203-214.

Van Neer, W. and Ervynck, A. 1996. Food rules and status: patterns of fish consumption in a monastic community. Archaeofauna Vol. 5: 155-165.

Zolnay, L. 1971. Vadászatok a régi Magyarországon (Hunting in old Hungary). Natura: Budapest.